One of the largest lakes in the world was situated here

TOLOKONKA, Russia: The geologists are digging in the bed on the western bank of what was once a 700-800 kilometre-long lake along the 62nd parallel in Russia. Large lakes, dammed up by a huge ice sheet one or more times during the last Ice Age, used to dominate this enormous plain.

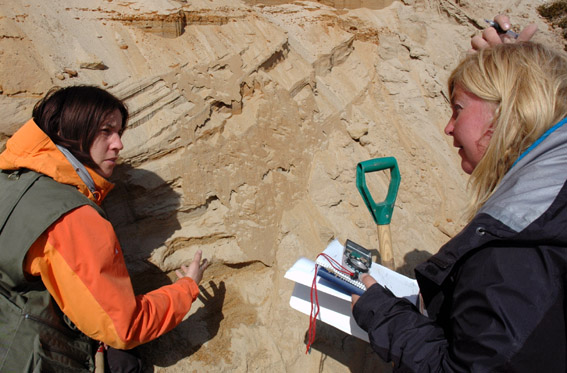

We are just beyond the ice margin from the maximum of the last Ice Age, where it has been mapped 100 kilometres north of the town of Kotlas in north-western Russia. Here, at Tolokonka, in a four kilometre-long cutting beside the River Dvina, an international team of scientists is busy studying the past changes in climate.

International cooperation

“Lakes have probably been situated here in two periods during the last Ice Age. We’ve found river delta deposits which suggest that the oldest lake formed some 65 000 years ago,” Eiliv Larsen, a geologist at the Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), tells me.

He is in charge of fieldwork being done in Russia as part of the SciencePub project during the International Polar Year. Along with colleagues from NGU, the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) and Hertzen University in St. Petersburg, he is continually finding new pieces to fit into the last Ice Age jig-saw puzzle.

Right on the margin

The enormous lake stretched from Kotlas in the west to the village of UstNem in the east, just a few tens of kilometres from the Ural Mountains. Last year, the scientists found remnants of a lake near UstNem. Now, the same lake has been found 700-800 kilometres further west, in the long cutting at Tolokonka. The mighty River Dvina, meandering north-westwards through the flat landscape to Archangel, dominates this region today.

“We’re trying to find out just what these lakes have looked like. Where did the sediments come from and how did the lakes influence the environment and the climate in the region? Even though we’re just beyond the ice margin, we’re finding traces of the snout of a glacier that calved into the lake from the north. This probably took place around 20 000 years ago and this was the youngest lake in the region,” says Eiliv Larsen.

The future climate

The scientists also tell me that it is very interesting to find out what took place when the ice finally melted, the dams burst and the enormous volumes of dammed up fresh water poured into the Arctic Ocean. This must have had consequences for the climate system and the oceanic circulation, for example.

“We ourselves are urged on by curiosity. When we started working in these parts of Russia 12 or 13 years ago, very little research had been done on the Ice Age. The results of our work now form part of the framework which climate researchers are using to calculate the future climate,” says Eiliv Larsen.

He generally uses a keyhole as a metaphor. “From a distance, you see hardly anything of the inside of the room, but the closer you manage to put your eye to the keyhole, the more of the room becomes apparent. It’s the same with the research here in north-western

Russia, we’re uncovering more and more of the Ice Age history and hence the past climate changes,” he says.