History rises from the ashes

BERGEN: Ash left behind after a volcanic eruption is filled with information on the volcano from which it derived. Like a fingerprint of the volcano, it remains in the sediments, well preserved for the future.

By Toril Berle Schalck

Professor Haflidi Haflidason is using a microprobe to analyse the chemical elements in a grain of ash.

- Just a small grain of this ash is sometimes sufficient to reveal the area from which the ash derived, which volcano was responsible and when the eruption took place, Professor Haflidi Haflidason from the University of Bergen says.

The ash has properties which makes it extremely valuable as research material. - It is easy to recognise, and it stands out from the other sediments, he continues.

Ash is the key

Professor Haflidason in the Department of Earth Science is participating in SciencePub, the research project that is part of the International Polar Year (IPY). This major research project will study the complicated interplay between climate archives on land, in the sea and in ice.

Ash from volcanic eruptions is one of the keys for understanding the interplay between these three archives. Down the ages, ash from volcanic eruptions has been transported rapidly over large areas. It is well preserved in the sediments and can therefore tell us something about the appearance of the landscape hundreds of thousands of years ago.

The research team from Bergen will not collect the samples, but will analyse them in the University of Bergen laboratories. The samples will be washed, and the tiny grains will reveal several chemical elements. Similar analyses have been performed earlier, but they will now take place on a larger scale.

The last 130 000 years

This is only a small part of this major research project, SciencePub, which will study the natural changes that have taken place in the Arctic climate and how the physical environmental conditions have changed over the past 130 000 years. The project will also look at how the first humans here adapted to the shift in the climate.

The scientists will reconstruct the past climate by studying natural climate archives preserved in sediments deposited in water and on land in Svalbard, north Norway, north-western Russia and neighbouring waters. The project involves a wide range of fields in geosciences and archaeology, as well as specialists to impart the information they acquire. Several scientific institutions in Norway, Russia and Copenhagen are taking part.

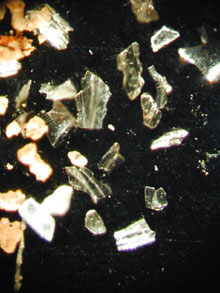

A grain of ash may look like this under a microscope. One such grain may be sufficient to reveal the area from which the ash derived, which volcano was responsible and when the eruption took place.